Scientists are researching the potential consequences of the rapid decline of the honey bee population in the U.S. and how to mitigate its effects before it causes dire problems for crop management and production.

Scientists are researching the potential consequences of the rapid decline of the honey bee population in the U.S. and how to mitigate its effects before it causes dire problems for crop management and production.

Honey bees are essential for the pollination of flowers, fruits and vegetables, and support about $20 billion worth of crop production in the U.S. annually, Matthew Mulica, senior project manager at the Keystone Policy Center, a consulting company that works with the Honey Bee Health Coalition, told ABC News.

Worldwide, honey bees and other pollinators help to produce about $170 billion in crops, Scott McArt, assistant professor of pollinator health at Cornell University, told ABC News. WATCH THE VIDEO

“Honey bees are one of the most important agricultural commodities in the country,” Geoff Williams, an assistant professor of entomology at Auburn University who also serves on the board of directors for the Bee Informed Partnership, told ABC News.

Over the past 15 years, bee colonies have been disappearing in what is known as the “colony collapse disorder,” according to National Geographic. Some regions have seen losses of up to 90%, the publication reported.

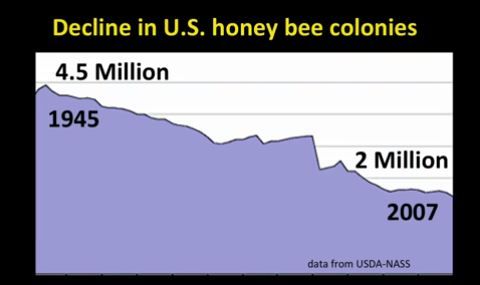

Data shows bee populations dwindling more and more each year

Between Oct. 1, 2018, and April 1, 2019, 37.7% of the managed honey bee population — colonies kept by commercial beekeepers — declined, 7 percentage points lower than the same time frame during the 2017-2018 winter, according to preliminary data from the Bee Informed Partnership, a nonprofit associated with the University of Maryland.

Between Oct. 1, 2018, and April 1, 2019, 37.7% of the managed honey bee population — colonies kept by commercial beekeepers — declined, 7 percentage points lower than the same time frame during the 2017-2018 winter, according to preliminary data from the Bee Informed Partnership, a nonprofit associated with the University of Maryland.

This past winter season represents the highest level of winter losses reported since the survey began in 2006, according to the report.

For the entire year — April 1, 2018, to April 1, 2019 — the managed bee population decreased by 40.7%, according to the report. The overall loss rate is around the average of what researchers and beekeepers have seen since 2006, McArt said.

“The main take-home from this is these are unsustainably high losses,” McArt said, adding that researchers are not necessarily alarmed at the numbers because they’ve become “a little bit accustomed to these large loss rates.”

The number of hives that survive the winter months is an overall indicator of bee health, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Worker bees tend to live longest during the winter — up to six months — and just four weeks in the spring and summer, according to the American Bee Journal.

Managed colonies are shipped around the country to pollinate our food

Much of the produce seen in grocery stores — watermelon, apples, peppers, cucumbers — and nuts are pollinated by millions of European honey bees, or Apis mellifera, that travel across the country and are managed by commercial beekeepers, Mulica said.

These U.S. crops are produced with the help of 2.6 million colonies transported by 18-wheelers from place to place during peak flowering, McArt said. Of the $20 billion worth of U.S. crop production supported by pollinators, commercial honey bees are responsible for about half. Wild bees and other pollinators take care of the rest.

In February, about 60% of managed colonies head to California to begin almond production, McArt said.

The bees then travel to Florida to pollinate citrus crops before making their way up through the Southeast for the production of blueberries, cherries and other specialty fruits and vegetables, McArt said.

Apple pollination begins on the Northeast in June, and the last pollination event typically occurs in Maine in late June and early July for lowbush blueberries, McArt said.

The bees then go to a set location for several months, where they gather nectar and produce honey, McArt said.

Why the honey bee populations are declining

The largest contributor to the decline of bee health is the varroa mite, a parasite that invades hives and and spreads diseases, McArt said.

“This is really a big knockout blow to a lot of these hives,” Mulica said.

Other reasons for the loss in population are loss of habitat and poor management practices, such as moving bees through the frigid Rocky Mountains during their winter journey to California, McArt said.

Incidental exposure to pesticides, pest and other diseases within the hive are also affecting the decrease of the population, Mulica said.

The populations of wild bees and other pollinators are suffering too, McArt said.

Food prices could rise if populations continue to decrease

While Williams does not believe honey bees are under threat of extinction, if their numbers continue to dwindle they could become a much more costly commodity for farmers, he said.

High bee losses year after year could lead to fewer beekeepers, and rental prices per bee colony could increase dramatically, Williams said.

This could also lead to steeper food prices, Mulica said.

“Really, what’s at stake here is rising food costs and the ability of beekeepers to deliver healthy bees to the crops,” Mulica said.

The first crop that may see a price increase with the decline of honey bees could be California almonds.

“We would not have almonds if it weren’t for honey bees,” McArt said.

The Golden State produces about 85% of the world’s almonds, Mulica said. But the cost for renting bees for almond production has increased to nearly $300 per colony in some cases, Williams said, when contracts for other crops in other states run about $80 to $150 per colony, McArt said.

The cost of colony rentals has not yet affected consumer prices for almonds, Williams said, but those costs could “eventually trickle down.”

How to slow down the bee population decline

All of the reasons for the loss of the honey bee population derive from human error, McArt said.

“Every single one of these stresses that we put on pollinators is man-made,” he said.

To save the bee population, researchers are looking into best management practices for beekeepers, such as how to treat hives for varroa mite, Mulica said.

They are also trying to figure out which pesticides could potentially be replaced with chemicals that are more bee-friendly, and what changes can be made to habitats to encourage more bees, such as planting wildflowers instead of green grass in the front yard and encouraging homeowners to mow their lawns less often, McArt said.

“I guess the question is, who’s willing to do these things, and how can we be more efficient in doing them?” McArt said.

U.S. government to devote less resources to bee research

The U.S. Department of Agriculture announced that it has suspended data collection for its Honey Bee Colonies survey due to budgetary reasons, just weeks after researchers reported that nearly 40% of managed honey bee colonies in the country were lost over the past winter.

“The decision to suspend data collection was not made lightly but was necessary given available fiscal and program resources,” a July 1 statement from the USDA read.

The USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service report is only one of three major bee surveys published each year, Mulica said. The Bee Informed Partnership and the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service also file reports that are widely used in the industry, he added.

Williams said it is “surprising” that the USDA made the decision to stop tracking the honey bee population, stating that it compounds the importance for independent studies to continue so scientists can understand the long-term trends of honey bees, not just for the sake of research but to allow policy makers to make sound decisions in the future.